Historical Background of the Santa Fe Trail

Trade was transpiring on the North American continent long before the arrival of Europeans. Along the Ohio River Valley where the Hopewellian Culture dwelled, we see evidence of Southwestern Pueblo designs starting from 1200 A.D. Likewise, evidence of Hopewellian designs exists in the Southwest.

Trade was transpiring on the North American continent long before the arrival of Europeans. Along the Ohio River Valley where the Hopewellian Culture dwelled, we see evidence of Southwestern Pueblo designs starting from 1200 A.D. Likewise, evidence of Hopewellian designs exists in the Southwest.

Juan de Oñate arrived in New Mexico in 1598. By then, trade between the people living around the present-day Texas panhandle and the Rio Grande Valley’s Pueblo villages was ongoing. Eventually, Spain, the mother country of Mexico and New Mexico, intervened.

According to Spain, trade was only legal if it benefitted the mother country. Trade with the Native Americans was deemed illegal, so the people of New Mexico were always in need of goods, and the goods that did reach them were expensive. In 1810, a short revolution took place in Mexico before being quickly suppressed. However, this initial spark against the colonial policy grew, and by 1821 the Mexican revolt against Spanish rule prevailed, making Mexico an independent country now free to trade with anyone.

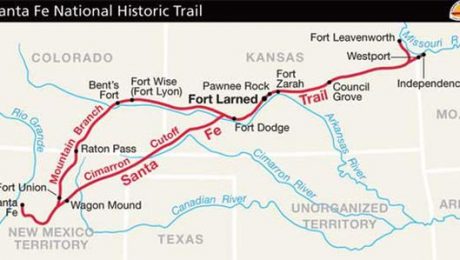

The Santa Fe Trail – America’s First International Highway

Wagons laden with cloth, needles, thread, knives, files, axes, and tools were headed for Mexico. There they would be traded for silver, furs, and mules, providing the traders a great return on their investments.

From 1821 to 1881, oxen and mule teams pulled wagons of commerce back and forth between Missouri and Santa Fe. The first successful commercial trip by William Becknell in 1821 opened this international highway between the United States and Mexico. In 1846, the U.S. Army followed the same path to occupy Nuevo Mexico and bring Santa Fe into the United States.

The railroad’s arrival into Santa Fe in 1880 marked the end of the trail, which had united two countries and two regions for decades.

THE FIRST SUCCESSFUL COMMERCIAL TRIP BY WILLIAM BECKNELL IN 1821 OPENED THIS INTERNATIONAL HIGHWAY BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES AND MEXICO

Becknell’s Trip

When Becknell headed west from Missouri in 1821, he followed a general route across the plains already trod by Native Americans, Spanish explorers and French traders. At the time Americans were not welcome in Spain’s far province of Nuevo Mexico. In fact, some Americans venturing to that territory had been imprisoned. But as Becknell traveled deeper into Spanish territory, he met up with a detachment of soldiers and was not arrested, but warmly invited on to Santa Fe. The reason: Mexico had achieved independence from Spain and trade restrictions had been lifted. His trip was a success beyond expectations.

Becknell and others headed out again in 1822. He used wagons on this trip, the first to be taken across the prairies to Santa Fe. Over the next several decades, thousands of wagons would follow.

International Highway

Traffic on the Santa Fe Trail was international. Besides wagons filled with goods often imported from Europe, those involved in the trade were of many nationalities. They ranged from French-Canadians like Antoine Robidoux to Germans serving as middlemen in the markets of Mexico. Hispanic merchants like Antonio Jose Chavez, the Armijo family, and the Oteros shared the trail with Americans like Henry Connelly, the Bents and the Magoffins. The commerce did not stop at Santa Fe. Traders very often continued south to Chihuahua and beyond. On the other end, Hispanic traders traveled eastward to markets as far as Philadelphia or New York to gather trade goods.

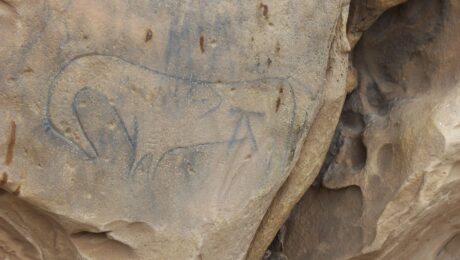

The trail also crossed the lands of Native American nations including the Pawnee, Arapaho, Cheyenne, Comanche and Kiowa. Traders dealt with these tribes providing manufactured goods in exchange for furs or horses. At times relations with the tribes were turbulent, especially as increasing trail traffic across the plains impacted resources like grass for grazing and bison for food. By the late 1860s, wagons crossing the plains were sometimes targets for the tribes, avenging military attacks on Native villages.

End of an Era

On February 9, 1880 the first railroad train arrived in Santa Fe. No more would freight wagons ply back and forth across hundreds of miles of prairie. In its time the trail had served as a conduit of not only goods, but of language, cuisine and ideas. This cultural exchange tied the Southwest to the rest of the United States. In recognition of the significance of the trail to our nation’s history, Congress in 1987 declared the Santa Fe Trail as a National Historic Trail. Modern travelers can still trace the ruts, visit trading posts and forts, and see homes of trail travelers here in Southeast Colorado.

A Trail Threaded With Silver

Money was there to be made in the Santa Fe trade. Bolts of cloth, canned goods, tools, firearms, ammunition, packed barrels of dried corn and apples, brass kettles, beads, and baubles moved west. Buffalo hides, beaver pelts, Navajo blankets, silver pieces, mules, and horses moved east. The trade on the Santa Fe Trail united two countries in trade.

One of the most wanted items in Santa Fe was cloth – calico, bleached, brown. Bought in St. Louis for perhaps 25 cents per yard, that same cloth could bring $5 a yard in Santa Fe. A large trade wagon full of cloth could make a man wealthy.

ONE OF THE MOST WANTED ITEMS IN SANTA FE WAS CLOTH – CALICO

William Becknell’s first trip to Santa Fe was with pack mules. Early traders used teams of mules or horses to pull their wagons. But eventually oxen were found to be more suited: stronger, less likely to break down, and not prized as an item to be raided by Plains tribes.

Teams of six or eight or even 10 oxen pulled the huge freight wagons loaded with goods, weighing in at 6,000 pounds. Drivers walked alongside the teams prodding them ever onward, 10, 15 or even 20 miles per day, on the 800+ mile journey for profits. (NPS photo)

In 1825, about $65,000 worth of trade goods were taken over the Santa Fe Trail to Mexican markets. In 1835, that number rose to $140,000; by 1846 it was $1 million; by 1859, $10 million; by 1862, $40 million!

800 Yards In A Day… Hardship On The “Mountain Branch” Of The Santa Fe Trail

The Santa Fe Trail broke into two branches in present-day western Kansas. The more traveled route, the Cimarron Branch, followed the Cimarron River, traveling through what is today the far southeastern corner of Colorado, the Oklahoma panhandle, and the northeast corner of New Mexico. This route was also known as the “Dry Route” since water was often scarce. Also, traveling through Comanche, Kiowa and Prairie Apache country, it could be more dangerous.

The other route, the Mountain Branch, continued to follow the Arkansas River, crossing that river in the vicinity of modern-day La Junta to reach the Purgatoire River and crossing the mountains via Raton Pass. Though more watered and safer, this route was longer and more difficult, especially crossing the pass.

Susan Magoffin, who kept a diary of her journey on the trail in 1846, wrote of the difficulties. From her diary entry for August 15, 1846:

… WE CAME TO CAMP ABOUT HALF AN HOUR AFTER DUSK, HAVING ACCOMPLISHED THE GREAT TRAVEL OF SIX OR EIGHT HUNDRED YARDS DURING THE DAY.

“Still in the Raton, traveling on at a rate of half mile an hour, with the road growing worse and worse . . . Worse and worse the road! They are even taking the mules from the carriages this P.M. and half dozen men by bodily exertions are pulling them down the hills. And it takes a dozen men to steady a wagon with all its wheels locked—and for one who is some distance off to hear the crash it makes over the stones, is truly alarming. Till I rode ahead and understood the business, I supposed that every wagon had fallen over a precipice. We came to camp about half an hour after dusk, having accomplished the great travel of six or eight hundred yards during the day.”

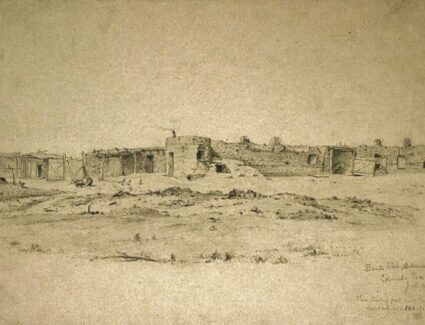

BENT BUILDS AND BURNS MASSIVE TRADING POST ON THE SANTA FE TRAIL

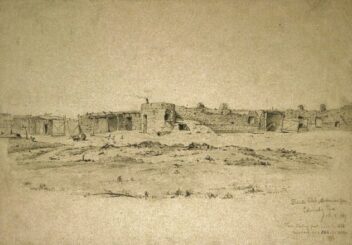

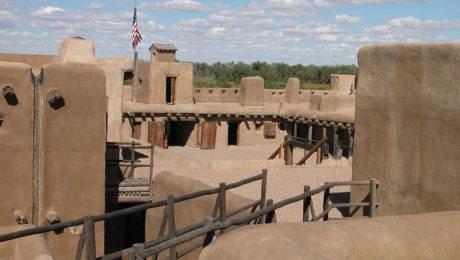

Opened by Bent, St. Vrain & Company in 1833, Bent’s Old Fort became the most prominent spot on the Mountain Branch of the Santa Fe Trail. Until 1849, this huge adobe trading post, looking to some like a castle dropped onto the plains, served tribes, traders, and travelers. William Bent managed the fort; hence it was often known as Fort William over its lifetime.

The fort was always a private, commercial operation. However, during the U.S. war with Mexico, the military used the fort as a supply depot (never compensating the company for this appropriated use). The war also negatively impacted the fort’s business. After the war, deaths in his family and a cholera epidemic among the Southern Cheyenne, the fort’s main customer base, led William to abandon the post.

THIS HUGE ADOBE TRADING POST, LOOKING TO SOME LIKE A CASTLE, DROPPED ONTO THE PLAINS.

As reported in the October 2, 1849, edition of Saint Louis Missouri Republican newspaper, on August 22 an eastbound party that included a Bent employee named Paladay, arrived at Bent’s Fort to find it abandoned and billowing smoke from a large fire. Though we will never know for certain what happened that August, most contemporary accounts agree that William lit the fire, which did not totally destroy the post. The fort later served as a stagecoach stop.

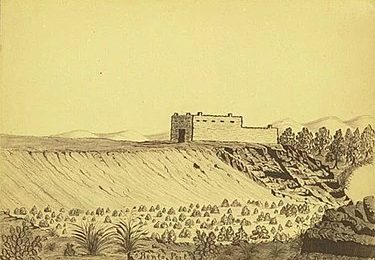

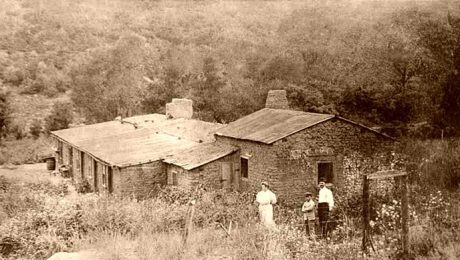

A few years later, in 1853, William constructed a new stone trading post on the Arkansas River at Big Timbers, west of present-day Lamar. This came to be called Bent’s New Fort. This post, leased to the U.S. Army in 1860, became part of the original Fort Lyon. From there, in 1864, Col. Chivington and his troops plotted and launched the attack today known as the Sand Creek Massacre. Three of William Bent’s children were living in the camp at Sand Creek. Over 230 Cheyenne and Arapaho were killed, but all three Bent offspring survived.

Uncle Dick’s Toll Road

The Mountain Route and its most important geologic feature, Raton Pass, played a significant role in travel along the Santa Fe Trail. Although the Mountain Route had been used since the 1830s, the torturous 7,835-foot, axle-breaking Raton Pass was both a barrier and a gateway.

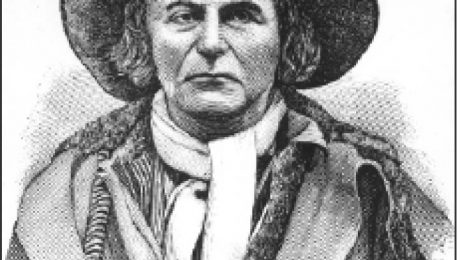

It was not until 1865 that improvements were made to this gateway by Richens Lacy “Uncle Dick” Wootton who made it “somewhat passable” for the stage lines. Wootton, after briefly operating a buffalo ranch near Pueblo, Colorado, had settled near Trinidad and leased land from Lucien Maxwell, owner of the Maxwell Land Grant, and obtained a franchise from the territorial legislatures of Colorado and New Mexico to build a 27-mile toll road over Raton Pass.

Wootton relied on the strength of the local Ute as laborers to build the road and thereafter allowed the Ute or members of other tribes to use the road for free. Others were charged $1.50 per wagon or buggy or 25 cents for a horse and rider to pass.

Being ever the entrepreneur, Uncle Dick then erected a boarding house, and the location of the toll gate soon became well-known as a “stage station, with provisions, liquor and weekly dancing.” This soon became the favorite watering hole for the young folks of Trinidad and the surrounding area.

A Murder on The Santa Fe Trail

As an international trading route, the Santa Fe Trail featured as many Hispanic traders as American, if not more. Antonio Jose Chavez, Ambrosio Armijo, Mariano Yrisarri, and Antonio Jose Otero freighted goods along with counterparts James Magoffin, Charles Bent, Henry Connelly and Sam Owens.

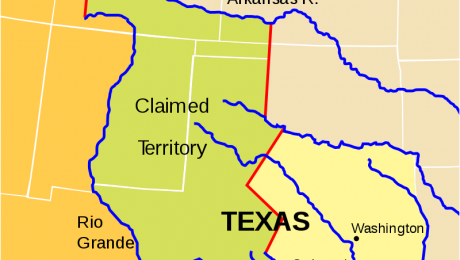

After Texas gained its independence from Mexico in 1836, hostilities continued as Texans raided Mexican parties along the Santa Fe Trail.

… HOSTILITIES CONTINUED AS TEXANS RAIDED MEXICAN PARTIES ALONG THE SANTA FE TRAIL…

Despite warnings of this, Don Antonio Chavez left Santa Fe in February 1843 bound for Missouri. On April 10, 1843 near the Little Arkansas River, well into American territory, Chavez was robbed and murdered by a band of ruffians led by John McDaniel. McDaniel may have been under the direction of Texas Colonel Warfield at the time. After the murder, the group split and headed for Missouri. Several were arrested there, including McDaniel who was eventually hung for his part in the crime.

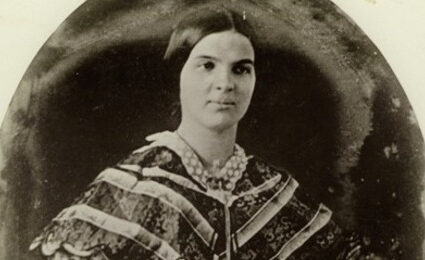

A “Wandering Princess” Travels the Santa Fe Trail

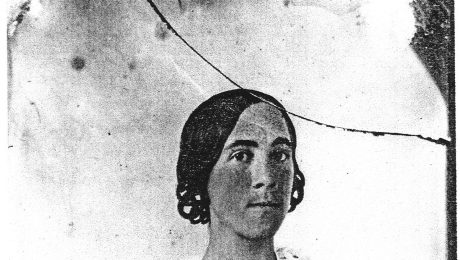

Susan Shelby Magoffin, the 18-year-old wife of merchant Samuel Magoffin, traveled the Santa Fe Trail with her husband in the summer of 1846. Her diary published as “Down the Santa Fe Trail and into Mexico: The Diary of Susan Shelby Magoffin, 1846-47” gives great insight into life on the trail. She wrote in her diary on June 15th, “It is the life of a wandering princess, mine.”

Pregnant, Susan traveled in a carriage on the bumpy 850-mile ride accompanied by her servant, Jane, and her pet greyhound, Ring. She wrote of swarms of pesky mosquitos and gnats, as well as the “ill-shapen…shaggy” buffalo. Her carriage overturned on the 4th of July; a few weeks later her tent collapsed on her in a storm.

Arriving at Bent’s Old Fort (“the outside exactly fills my idea of an ancient castle”), Susan was feeling ill. Her 19th birthday took place at the fort. While there, she sadly suffered a miscarriage. Meanwhile she writes of a Native American woman giving birth in a room below her and taking the baby to the river to bathe within a half hour of giving birth.

THE OUTSIDE [OF BENT’S OLD FORT] EXACTLY FILLS MY IDEA OF AN ANCIENT CASTLE

After a stay of 12 days at the fort, Susan’s husband’s caravan moved on toward Santa Fe. They later traveled further south into Mexico as part of Samuel’s business. Returning to the States in 1848, Susan passed away in 1855 and is buried in St. Louis.

Susan’s diary in published form is still in print and available from many booksellers.

Images: Susan Shelby Magoffin (partial ambrotype from collection of Mark Lee Gardner) and Susan’s recreated room in the upstairs corner of the fort “…we have two windows one looking out on the plain…” (NPS photo)

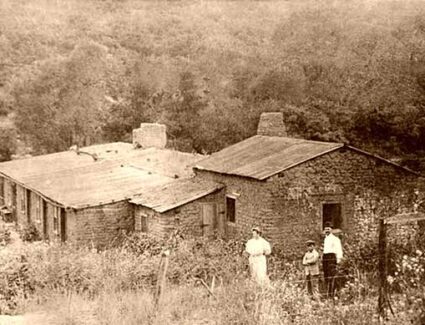

Recipes From Charlotte’s Kitchen

Charlotte and her husband Dick were enslaved people owned by the Bent Family who both worked at Bent’s Fort. This being pre-Civil War days, that “peculiar institution” had yet to be abolished. Lewis Garrard, another visitor to the fort noted Charlotte as “the glib-tongued sable Fort cook” and a “culinary divinity.” She was also reportedly the “belle of the ball” during Fort fandangos.

Charlotte and Dick were last known to be traveling back east on the Santa Fe Trail later in 1847, as reported by Garrard, having been set free due to “the valor evinced by the latter, Dick, at the Pueblo de Taos.” That was the fight to put down the Taos Revolt in which the first American governor of New Mexico, Charles Bent was killed.

CHARLOTTE AND DICK WERE LAST KNOWN TO BE TRAVELING BACK EAST ON THE SANTA FE TRAIL LATER IN 1847

Following are a couple of recipes that would have been at home in Charlotte’s kitchen, courtesy of Sam’l P. Arnold, founder of the famous Morrison restaurant, The Fort, in his book “Eating up the Santa Fe Trail.”

Pumpkin Pie

1 ½ cups sugar

½ teaspoon salt

1 ¼ teaspoons cinnamon

2 eggs

2 cups pumpkin puree (cooked fresh pumpkin, beaten or from canned)

1 ¼ cups milk

Mix dry ingredients together, then fold in eggs with whisk. Add pumpkin and whisk well. Add the milk and mix in. Pour into a 10-inch pie shell and bake (at 350 degrees) for 1 hour and 25 minutes. Serve with whipped cream or ice cream.

Slap Jacks

Take and scald a quart of Indian meal (a.k.a. cornmeal as would be used in grits or cornbread) in milk if you have it – water will do. Turn it out and stir in a half-pint of yeast (a package of dry yeast in a cup of warm water), and a little salt. Fry them, when light, in just sufficient fat to keep them from sticking to the frying pan. Another nice way: turn a quart of boiling milk or water into a pint of Indian meal, stir in three tablespoons of flour, three eggs, and two teaspoons of salt.

The kitchen at the reconstructed Bent’s Old Fort National Historic Site. Here is where Charlotte practiced her divine culinary skills. Some of the hearthstones are original to the site, the very same that Charlotte herself walked across.

“Eating up the Santa Fe Trail” by Sam’l P. Arnold, famed restaurateur of The Fort in Morrison, Colorado. Besides great recipes from the days of the Santa Fe Trail, this book shares stories and history that bring trail days to life.